Context & Challenge Obstetric Violence. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth.

We come to the world crying, covered in blood and bodily fluids. Although it is usually romanticized, childbirth is a noisy, messy, violent—but natural—event. This kind of violence is unavoidable, it is part of the circle of life.

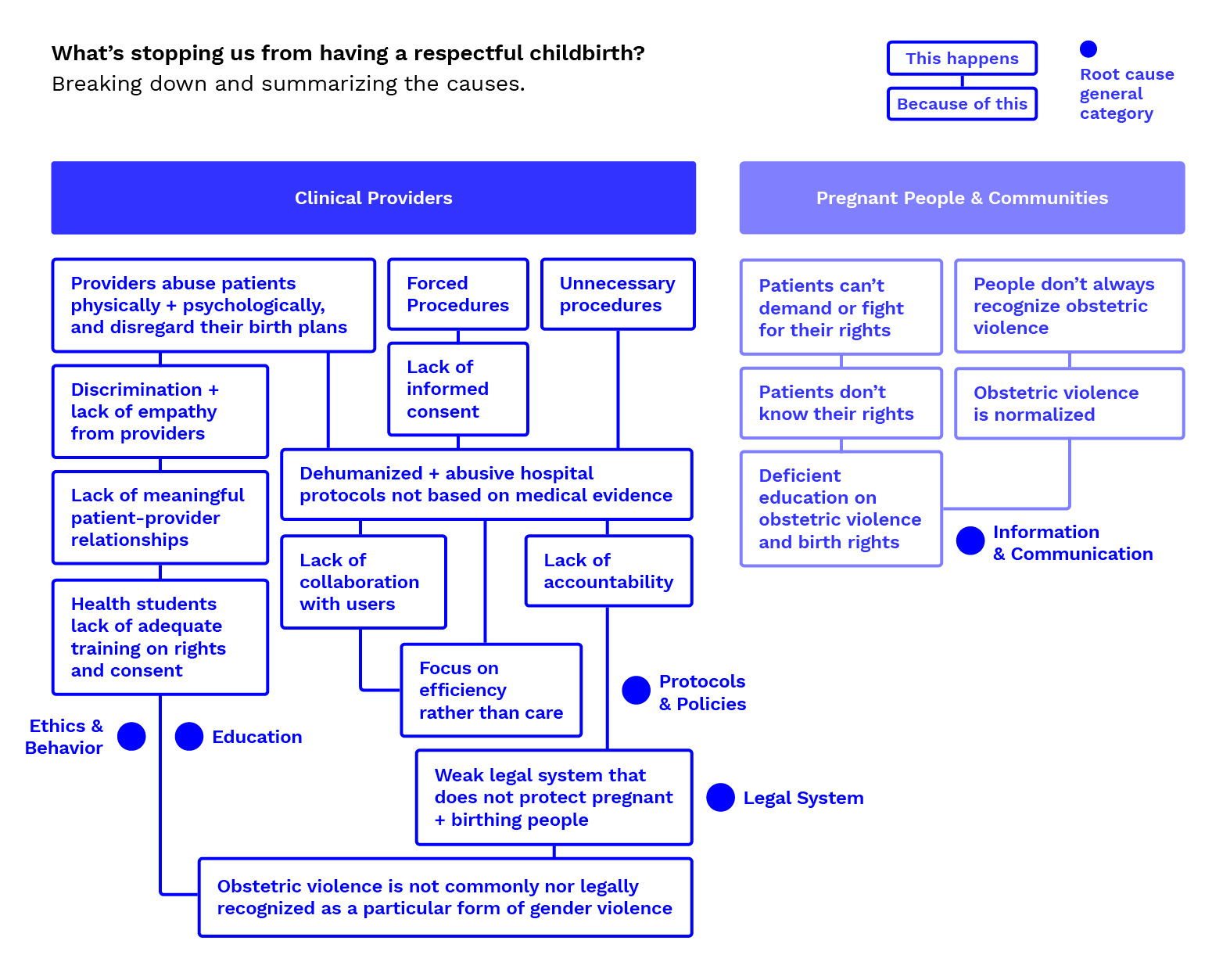

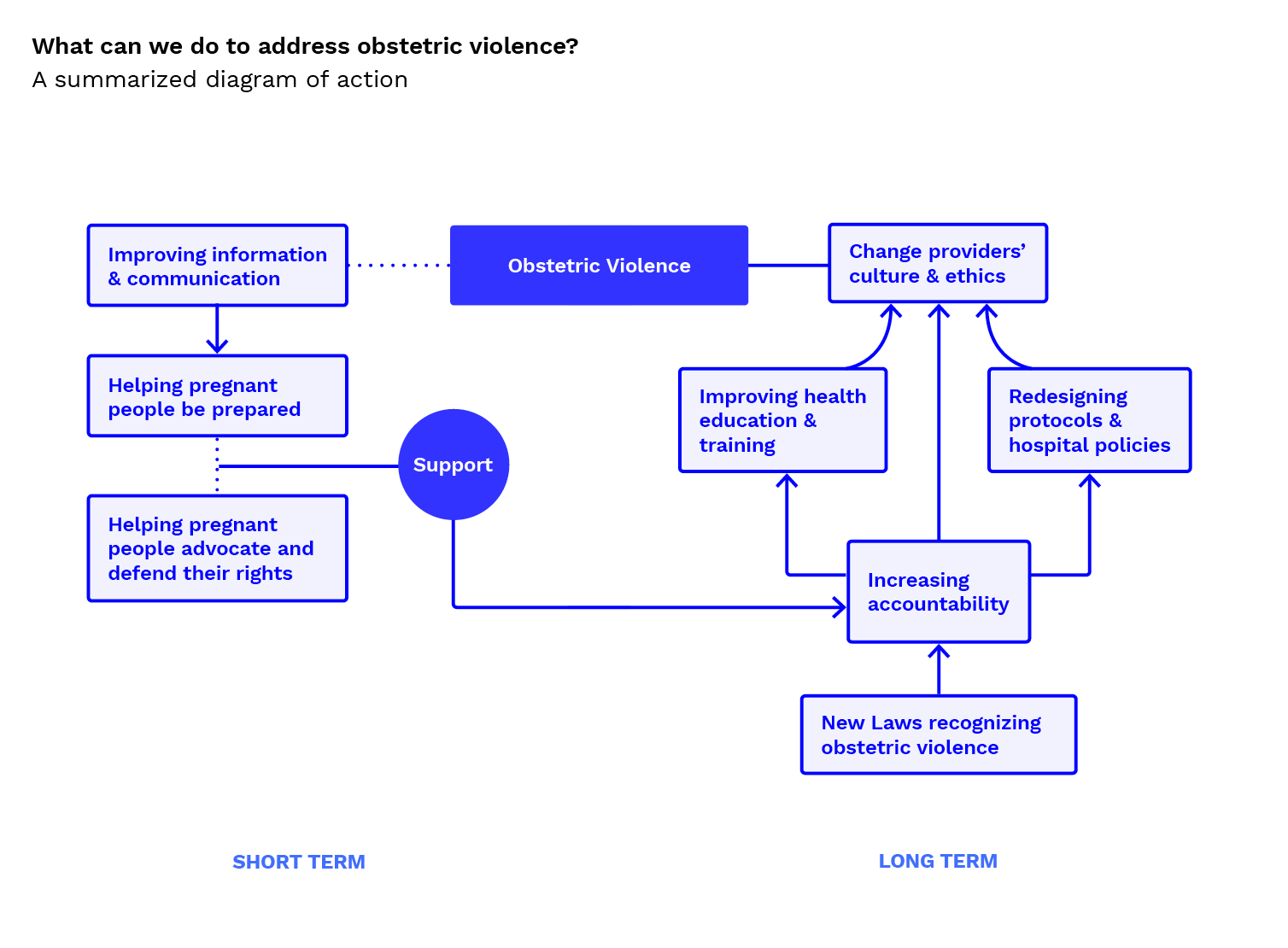

However, labor and childbirth is often also accompanied by a common, invisible, and avoidable type of unnatural violence: obstetric violence. A normalized set of practices that relegate birthing people to a secondary plane, focusing solely on the well-being of the baby while infringing on people’s fundamental rights of dignity and respect, making the experience of childbirth traumatic for many of those who go through it.

1/3 of pregnant people in the US report having been victims of obstetric violence.1

In a society where medical practice is often shaped by efficiency rather than by care, giving birth, a normal physiological process, became highly medicalized. Over the years, the rates of cesarean section, use of oxytocin, episiotomy, epidural, enema, electronic fetal monitoring, intravenous infusions, among other medical practices, have increased and have even become routine.

Today, as high as 30% of childbirths in the US are C-Sections (double the World Health Organization recommendation), half of which are not medically necessary, putting patients in danger2.